In Conversation With… Ruby Wax

My childhood was so crazy it veered into funny. I mean, I’ve written books about it and when Carrie Fisher read my work, she said my parents were almost as bad as hers – well, that’s one kind of review I guess. If anyone tries to throw their cards on the table about how bad their childhood was, I can always throw mine straight back. My parents were immigrants from Vienna, but they never mentioned having left Austria [in 1938] – it was only their accents which gave them away… they always sounded like they were declaring war on Europe. But in terms of our family, there was very little information which was shared.

My parents personified the typical immigrant story. Once they had enough money, they moved out of the city to a suburb of Chicago called Evanston, which is where I was born. They were living the American dream – albeit with German accents and typically American outfits and witticisms. My dad would always say: “Dat’s da vay da cookie cvumbles!”

There were never any clues given about our Jewish heritage. My relatives were never mentioned – instead, I mainly received cleaning instructions from my mother, while my father relentlessly told me about my many failures. I was an only child and it was very intense – although there was a determination on my part to prove I wasn’t a loser. If you ask me, if you treat your child like a loser, they’ll probably turn out to be a loser to some extent.

They thought letting me go to drama school in the UK was cheaper than a mental asylum. That’s a true story – I heard them discuss it. When I arrived in Glasgow [at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama], I was completely alone – I knew no one. I’d previously come to Europe for finishing school at 16, but I ran away to England. My parents sent me a dollar through American Express, but thankfully it cost nothing to live in the UK at that time – and especially Glasgow. It got me off their backs for a while – at least, I think that’s how they looked at it. Even so, their plan was for me to go home after drama school and my dad would set me up with a job in linens because he didn’t think anyone would marry me. That thought helped propel me into the Royal Shakespeare Company after I graduated.

My time at the RSC was such a thrill. Don’t get me wrong, I wasn’t given big parts in the beginning (ash tray number one, seaweed etc) and when my parents came to see me in productions (which they did four times a year) they told Alan Rickman he had made a mistake by casting me or directing me. The truth was I was a terrible actress, and I felt the same loathing from the audience as I did from my parents – but I knew it would at least keep me safe from having to go back to the linen industry for a while.

My foray into comedy was all down to Alan. We were sharing a house at the time, and he told me to write the way I speak and turn it into a play. It was really he who turned me into a comedian. The play wasn’t very good, but it helped me get my own shows and documentaries – including the pilot for Girls On Top [Ruby played American actress Shelley DuPont]. As an actress, I could never remember lines, but Alan had a way of writing things down for my comedy shows that made it feel more natural. Only recently did Juliet Stevenson tell me how proud he’d been of me.

Alan’s death [from cancer in 2016] wasn’t a ‘trigger’ for me mentally speaking. That’s not the way depression works – it’s an illness, and something I’ve experienced since childhood on and off. When I lost my job on television – let’s face it, I turned a certain age and that was that – it was during a bout of depression which I’d been tackling for a number of years before that. Interestingly, I’m making a bit of a comeback to television this August on the BBC. They’ve supported me for nearly 25 years and there’s a programme due to air all of my ‘best bits’ if you like. It just goes to show it’s better to reinvent yourself after they kick you out.

It’s a common misconception that comics are always depressives. I’d say many of them are neurotic or narcissists, but the fact is one in four people are depressives and they’re not all comedians. If you think there’s a link between comics putting on a ‘happy face’ and battling darker demons behind closed doors – well, that’s acting for you I suppose.

I’ve been running my mental health charity Frazzled Café for five years now. It’s my baby, and while I didn’t used to run the meetings (they would happen in cafés up and down the country) I took over a lot of the sessions during lockdown. It gave me such insight into a broad cross section of people, and how they were reacting to this new reality. The consensus was we’d all been so protected and removed from reality, so people were truly taken by surprise by the events of last year.

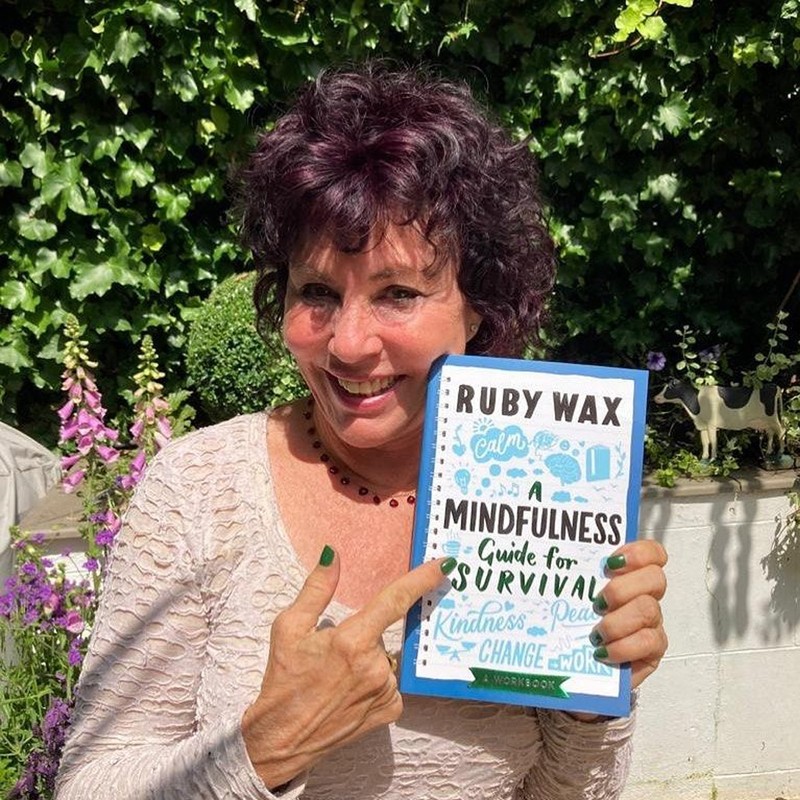

Dealing with this new reality is what will help us be more resilient if it happens again. This is a lot of what my new book is about – using mindfulness to unpack and pick apart elements of what I call the six realities: difficult emotions, uncertainty, loneliness, change, dissatisfaction and death. But it isn’t just about how to get through a pandemic – or even the fall out. It’s a wake-up call to confront the idea that reality is changing all the time, whether you like it or not. It’s happening now and change is inevitable. For now – at least until technology catches up and is able to give us real-time biological feedback – mindfulness is the best route to get an internal view of yourself. It’s why they’re teaching it at Oxford now and not witchcraft.

While we might be in different boats, we’re in the same storm. It’s just about dealing with it with your eyes open. Even though the book isn’t designed just to get people through the pandemic, it felt like I had to publish it now in case we all start to forget what we’ve been through in a year’s time. Do the work now, and you’ll be far better equipped to deal with similar events in the future.

My three children deal with mental health in a completely different way. My two girls are comedians, and my son is a coder, but they’ve always been taught not to be afraid of mental health or the discussion around it. My husband Ed’s genes are really good, too – his family were army people and I think that has a lot to do with how resilient our kids are. Ed and I got married in 1988. We met during Girls On Top when he was brought on as director; I tried to get him fired because I didn’t think he knew what he was doing. If you want to know the secret to a long-lasting relationship, it’s having your own sense of autonomy. I don’t need him to travel with me all the time and I can’t expect him to be interested in all the same things as me – this is also what the book is about: you’re alone babe, so start dealing with it.

Being alone or loneliness is very different to isolation. And the way we cope with both is entirely different. It’s one thing to be okay with your own company, and another to feel like you’ve been shut or closed off from the world and your community. It’s something you have to negotiate with yourself – and find a new community if you think it will help. I always say if you’re seriously mentally ill, then take the medication if you can get it. Otherwise, we just have to learn how to get off our own backs. If you don’t like being lonely, do something about it.

Our reality only changes more the older we get. If doesn’t matter if you’re old as long as you’re interesting – so, do what you want to do and do it now. Assuming things will always stay the same is the danger here, but you can’t be scared of it. Change is coming and it’s only the mental anguish we put ourselves through which is the manmade part. You have to exercise your mind like you’re going to the gym – that’s what it’s all about.

If I could tell anyone older anything it’s this: there is a way out and you don’t have to be stuck with the baggage of who you are. Case in point: I failed at school but then went on to study at Oxford in my 50s. When you’re doing something because you really want to and not because your parents are shouting at you to do it, your neurons actually grow.

‘A Mindfulness Guide To Survival’ is available at Waterstones.com and all good bookshops now. For more information visit FrazzledCafe.org and follow @RubyWax on Instagram.

DISCLAIMER: We endeavour to always credit the correct original source of every image we use. If you think a credit may be incorrect, please contact us at info@sheerluxe.com.