The Gold Edition Meets… Lindsay Nicholson

Most people should only write one memoir. You do not really want to have a life where you end up writing more than one. My first – Life on the Seabed – which came out in 2005, was an exploration of grief or what I thought at the time was long-term grief. It was 13 years after my first husband, John, died and seven years after my eldest daughter, Ellie, also passed away. I thought I was through it and had found my happy ending with a thriving career, a second marriage and raising my second daughter Hope.

Even a couple of years later, when I’d gone through breast cancer, I didn’t feel moved to write a second memoir. Regrettably, breast cancer is extremely common, and so I didn't think I had anything particular to say that other people weren’t already saying. Then, the events of 2016 and 2017 happened.

It makes sense to start at my 60th birthday party in 2016. It was in London, there were 100 people there, including my husband who made a glowing speech about his love for me. I was riding high in my career – Good Housekeeping was the biggest selling lifestyle magazine in Britain and I'd won lots of awards. Part of the reason for having such a big party was to thank all the people who had been with me all the way through since the events of the 1990s.

One month later, on 30th October 2016, I’m driving home from visiting my mother. I'm involved in a terrible headlong crash at 70 miles an hour with a lorry that jack-knifed across the road, which was caused by someone attempting to take their own life by running in front of it. The driver swerved and hit me. I took some time off work, which was very unusual. During all the things that have happened in my life, I’ve always gone to work. I loved work – it was my safe space – but this time, I couldn't stop crying and couldn't do my job. I took ten days off – longer than after my husband died – but I could still tell something was wrong; I just didn't know what it was. I later discovered the crash had sort of unblocked all the trapped grief that had been there for 20-25 years. I had coped so well and then, I just stopped coping.

Around the same time, my husband started behaving strangely. I didn't understand it, but I couldn't really focus on it because I was so overwhelmed by all the other feelings I was having. Then, in February 2017, I discovered he was having an affair. I confronted him but I didn't do it very well because I was struggling with this PTSD from the crash. I was seeing my doctor, I was on antidepressants, I was getting help, but it was enormous. I tried to look at his phone for proof of the affair. At first, he wouldn't let me, then he let me, then the phone fell on the floor and broke. That was when he called the police who arrested me and kept me in a cell for 16 hours. Earlier that day I'd actually been deeply suicidal, so to be struggling with those thoughts and PTSD, being locked in a cell for 16 hours was a pretty dreadful combination.

I hadn't done anything wrong, but it was still a very shaming experience. When I looked into it, I discovered that women are three times more likely than men to be arrested after an accusation has been made. Even though the statistics show that these cases never come to court. There are women losing their homes, children losing their homes because of this. The best way I can put it is there’s this tendency for police officers to arrive at a scene and assume the most unusual circumstance rather than the most usual circumstance. That felt really wrong to me.

I moved out of the house with my daughter Hope on the advice of my solicitor. I went back to work but, in July 2017, I found out I was being made redundant. The company was actually very decent about it and treated me fairly. It was a business decision after all, but I loved work so much, so it was very painful for me. Then, I got evicted from the house I was renting. So, in the space of a year from the crash, I found myself getting divorced, made redundant, homeless twice and arrested. That was rock bottom.

The good news is I’m in a far happier and better place than I was. I realise now I was covering up my grief with workaholism. The thing is the noughties were an absolute golden period of print magazines – absolutely amazing. I’d worked in magazine since the late 80s and early 90s – when the editor of a glossy magazine was considered queen of the world. But it was never really about what magazines could give to me – I just loved it, even when sales would ebb and flow. I was fortunate to catch a wave – in 2005, more print magazines were sold in this country than almost anywhere in the world, except the US. We had no real online competition, either. People often ask if I’d still like to be an editor now and the answer is, not unless I can get in a time machine and go back to 2005. That was when budgets were big, the shoots were incredible – but then technology moved on.

You could start to achieve effects with Photoshop and the cost of paper and printing also went up. But I wasn’t worried – I would work with whatever the prevailing conditions were. I probably didn't see they would get as difficult as they were or that I would be expendable. I also thought because I was 60 that it would see me out – like Anna Wintour, who's always been a heroine of mine. But after I was made redundant, I was in such a bad way psychologically, I wasn’t able to interview for other jobs.

I’d gone back to work right after John's funeral in the early 90s. I was pregnant with Hope, my second child and Ellie was three. It’s quite a thing to walk into an office and everyone knows what's happened – many of them were at the funeral. You’re a conspicuously pregnant widow. There were a few people looking away because they didn't know what to say. But that lasted about half an hour because of the deadlines, because of the pressure – everyone forgot to be peculiar around me and I forgot to be peculiar around them. I had eight to ten hours a day when I didn't have to think about what had happened. Work became where people treated me normally. They judged me on results, not on what was happening in my life or the grief I was feeling. It became very addictive.

One thing I really didn’t pay enough attention to at the time was the breast cancer. I was diagnosed two and a half years after I married Mark, and it was shocking. Any cancer diagnosis is awful but, given what had happened to John and Ellie – both of whom had died of blood cancer – I assumed I was going to die. While I'd had to deal with these terrible things in life, I hadn't had to deal with my own body failing. I’d always believed I’d be able to work and take care of my surviving child. But breast cancer took that away from me. I’d believed all the bad stuff was behind me, but it wasn’t. I say all of this in hindsight, because I didn’t see it at the time.

I should have slowed right down and rethought my life back in 2007. But I didn't. What I did was get really angry with myself, with my body and just worked even harder. I'm not saying I should have given up work, but I was 50, so I could have perhaps looked at pursuing a career path that would have seen me further into the future. As a result, I missed a lot of what was happening around me – like my husband not being where I thought he was, that my job was not going to see me out.

It never crossed my mind that I would be involved in an acrimonious divorce. I had no clue that such a thing could happen to me. I would have thought I’d fight with every fibre of my being not to get divorced but, if divorce became inevitable, I’d never have thought it would be acrimonious. Nobody goes into a marriage wanting an acrimonious divorce. It’s a very strange feeling because the person who you would most want to talk to about it has become this stranger who is the cause of your distress – you barely know up from down or which way to turn. You're very confused, so once someone finds themselves in that situation, I don't think you can blame them for what they do to try and get a handle on it. However, what I would say has really surprised me – the act of being betrayed is really cathartic. While nobody wants to be betrayed, it tells you who you are and forces you to look at things in a way you wouldn’t have before. It forces you to ask yourself how this happened, and then you realise that, in some way, you betrayed yourself. I betrayed myself by thinking work was the answer when it wasn’t.

Now that I look back on it, I can see that the redundancy was probably a bit of a blessing. I have a really fulfilling life now – I'm a non-executive director of a university and the chair of governors at an adult education college. I write, I volunteer with Riding For The Disabled. I see things and experience things now that I didn't even know existed when I was an editor. And they're so rewarding. I'm also a grandmother now, so I get to look after my granddaughter Cora one day a week. Much as I loved my work, the nature of the job wouldn't have given me any time to explore all these other things. There's so much more to life really.

I wouldn’t say I have regrets, because regret is really self-blame. That’s not particularly helpful. I’m glad I had the optimism at the time to get remarried – I’m glad Hope and I weren’t alone when I was going through breast cancer. To this day, they still have a good relationship. The only thing I’d say, which is more of a learning, is that if there’s a crisis in your life – and breast cancer was mine – use it to reevaluate your life. It can be a gift – an opportunity to take stock, not double down on work. While I did things that were tremendously satisfying at Good Housekeeping, it was at a great expense to myself. I’d like to think now that, if a crisis happened and once the initial shock was over, I would take that as an opportunity.

Ironically, I think what really saved me was magazines. Not at first – when I first hit rock bottom, they were dead to me. But then I was just playing around one evening, remembering the sorts of jobs that I used to do – the coverlines for example – and I started writing anti-cover lines like ‘Dress like nobody's looking at you’ and ‘101 reasons not to exercise, you need only one’. I kind of made myself laugh doing that. And then I realised I’d spent years telling women how to live their life but I wasn't living my life. I wasn't following any of the advice in the magazines. So, I made myself a little plan, like the plan on the cover of a magazine.

The first thing I wrote down was cook yourself happy. I started by cooking myself a proper supper every night. Everyone thinks you should be able to do that, but it's actually quite challenging. You have to shop, plan, cook, then it goes a bit wrong, so you have to find another recipe. But it became a creative project. By this time, we were in lockdown, so I really started to enjoy it. I’d also spent some time in California and had seen horses being used in therapy. That’s not really done very much in this country but Riding For The Disabled is very big. We have a great stable nearby, so I started volunteering there. I'd ridden as a child, but I had no skills. I was put on the muck shovelling duty, and it was fine. So, I was eating proper food every evening and, every morning I would get up and go to the stables. I was outside in the fresh air and part of a team helping people who, frankly, had far more difficult and problematic issues to deal with than I had.

I also started to ghostwrite for other people. Those were really the foundation stones. If someone came to me now and said, “My husband's cheated on me and I've lost my job, what should I do?” I'd say go for a walk in the fresh air, cook yourself a decent meal and find a charitable cause to volunteer with. Those are the cornerstones of a sane life. I'm a big fan of doing things where you can't easily get your phone out. After getting involved and training with Riding For The Disabled, I bought a horse and the great thing about riding is that you can't start scrolling or you will fall off. My mother, who is 89, also gardens and I truly think it’s the secret to her longevity.

I struggle with the word resilience. It’s bandied about and people find it very hard to articulate what it is. They're very quick to point to people and say, “Oh, they lack resilience or if only they had more resilience.” I think resilience is quite often more defined in its absence than in its presence. And no one really knows quite how to achieve it. Of course, it’s what we would all aspire to and I suppose that’s the point of the book – to show that resilience doesn't come from one thing, be it the amazing therapist, a brilliant childhood or awards. It’s actually in the tiny details, in the way you live your life. It's going for a walk, making yourself a decent meal from scratch, finding a cause to which you can commit whatever time you have. It’s not going to change your life by next week but, if you do that consistently, you will be strengthening yourself inside.

Crises will continue to happen. No one is going to have a crisis-free life but, if you've got that bedrock of the little actions, it will buy you enough time to take a deep breath, see where you need to change direction a little bit and see what's working and what’s not. When I was made redundant, I hadn’t eaten or slept properly in years. I had no sense of purpose other than working in a commercial organisation. I had no sense of what I could offer, no idea that I had a valuable place in the community. But if I’d paid the breast cancer the right attention, I’d have thought maybe I could make some changes here. These days, social media will tell you there are five ways to change your life. But it's not true. You need to do the small, quiet things over time.

Out there, in the real world, a lot of people are dealing with a lot of stuff – and they're doing it with grace and dignity. I'm not special. The only thing that's special is that, because of the job I had, I was able to produce this book and talk about it. A lot of people have had things a lot harder to deal with than I had. When you slow down, you start to find that life is so remarkable and wonderful in a way that, when you're hurtling along so fast, you don’t realise how much you’re missing out on.

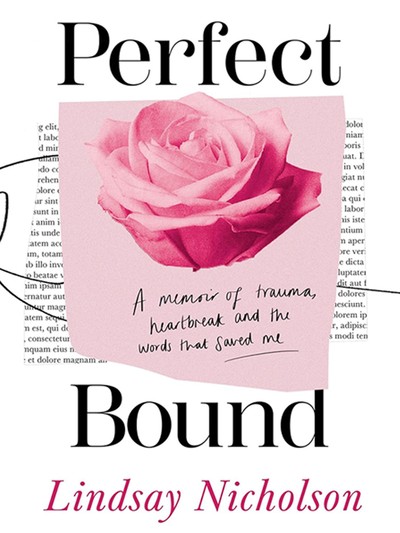

Perfect Bound: A memoir of trauma, heartbreak and the words that saved me by Lindsay Nicholson is published by Mudlark on 18th July 2024. Pre-order at Amazon.co.uk.

DISCLAIMER: We endeavour to always credit the correct original source of every image we use. If you think a credit may be incorrect, please contact us at info@sheerluxe.com.