Chapters In My Life: Claudia Roden

Chapter One: Growing Up

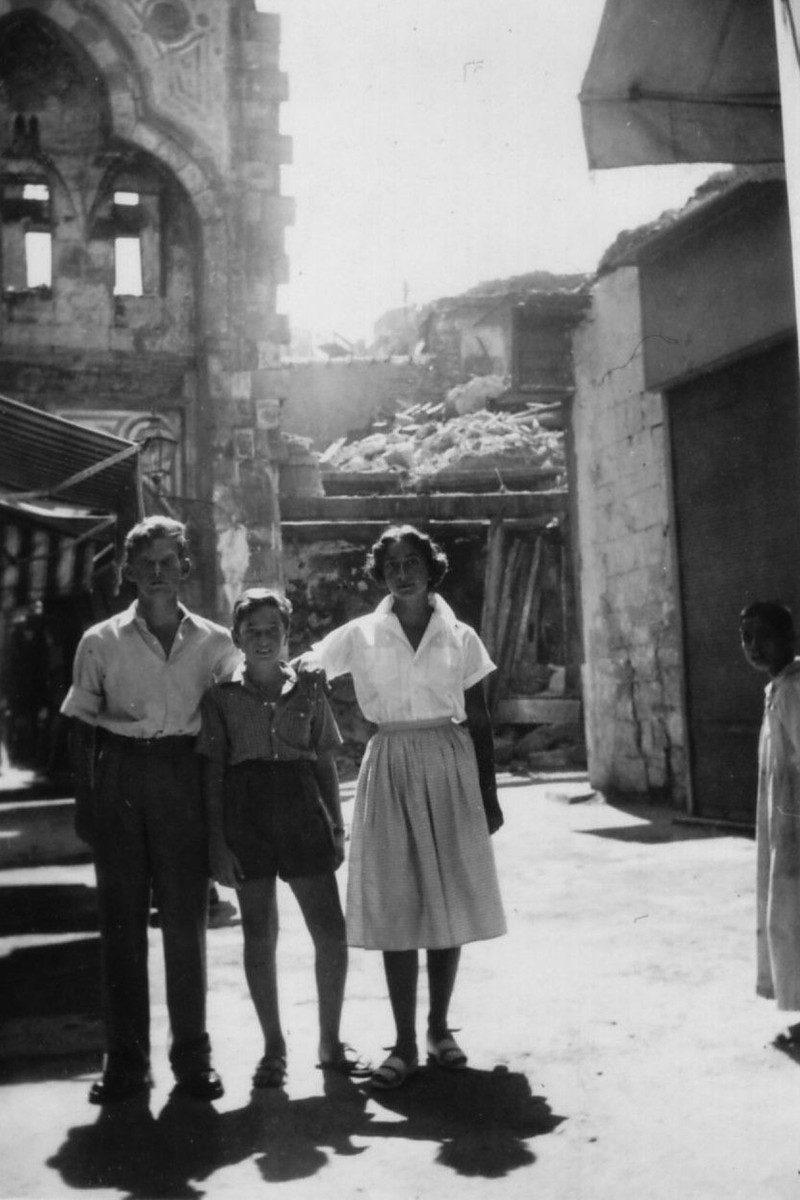

“I was born in Egypt in 1936. I come from two large extended families – the Doueks and the Sassoons. I lived with my parents and two brothers, Ellis and Zaki, in a flat in a residential area of Cairo overlooking the Nile from where we could see the boats glide by. Three of my grandparents had come to Egypt from Aleppo at the end of the 19th century when the Suez Canal was built and Cairo became a mercantile hub; my maternal grandmother came from Istanbul. We had a cook and a Slovene-Italian nanny called Maria, and we cooked Syrian, Turkish and French food, and Jewish dishes on festive occasions. Maria cooked for us separately when we were small children and her dishes were very Italian as she came from an area of Slovenia near Friuli that was part of Italy at the time. Our way of life was very simple, mainly visiting and entertaining a lot, as there was a culture of hospitality and food was all important. On special occasions and for big events, aunts came over and brought their cooks with them, and we sat around a table while the cooks were prepping in the kitchen. We were rolling vine leaves, folding filo triangles and making all those things that require time. We also went to the club a lot and we swam – it was like an English-style club where you could play golf and everyone there spoke French. I was a swimmer and used to train regularly.

“In 1951, when I was 15, I was sent to boarding school in Paris. My brothers were already there. The school was a big lycée but us boarders lived in a large villa in the Bois de Vincennes. The food was simple but extremely good and, in the evenings, we had three-course meals with wine and beer. It was homely French food, so I got to know what people cooked in their homes in France. The boarders mainly came from the colonies – from Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco and French Equatorial Africa, as it was known then – and we had lots of laughs around the table, throwing things at each other and mixing things that were disgusting!”

Chapter Two: Coming To London

“In 1954, I came to London to study art at St Martins. My brothers were already here – Ellis was a medical student and Zaki was at the French Lycée – and we lived together in a flat. I used to cook for them and our friends. At the time in Britain, the food was horrible! It was brown, beige and not very flavourful – and it was difficult to buy the ingredients I needed to cook our kind of food. I had to go to Camden Town to a Greek-Cypriot grocer called Mrs Haral to buy bulgur, chickpeas, tahini, pomegranate molasses and rose water. I also went to a place in Kentish Town to get kadaifi and pitta and to watch them make filo by hand.

“In the end, I only had two years at art school. In 1956, there was the Suez crisis and the Jews were forced to leave Egypt in a hurry. My parents came to London to join us and we were refugees; they had to leave everything behind and I had to leave art school and earn a living. That is also when I started collecting recipes. I had no wish to become a food writer but I just collected them for us because there hadn’t been a single cookbook in Egypt, no printed recipes at all and nobody would ever have imagined looking up a recipe. There were waves and waves of relatives and friends arriving, thousands of them, and they were put up in different places until they could find a country to settle in. I felt collecting recipes was the most important thing I could do. They were the most important part of our culture and our legacy – something to hold onto that would otherwise be lost forever.

“It was a mixed bag of recipes because the Jewish community in Egypt was a mix of families from all over the Ottoman world and around the Mediterranean. I became obsessive, every recipe was precious, and everyone wanted to give me theirs, whereas back in Egypt no one would have passed one on outside the family. But here in London, we thought we would never see each other again, so they were something to remember one another by. To this day, I can recall the voices and faces of these people, and I smile when I cook their recipes.

“All the recipes came from women my mother’s age. They would tell me that their recipe came from their mother in Izmir, their grandmother in Istanbul, their aunt in Aleppo, and I realised what kind of community we were and that we didn’t just cook Egyptian recipes. After leaving art school, I was working at Alitalia reservations in Regent Street – I got paid £7 a week but I was allowed to travel for free whenever there was room on a flight so I kept going to places whenever I could and would find other Egyptian Jews who had landed there, and they would pass on their recipes too.”

Chapter Three: Marriage & Family Life

“I met my husband Paul in a café in Hanover Square near where I worked, and we got married a year later in 1959. I had three children: Simon was born in 1960, Nadia came soon after in 1961, then Anna was born in 1965. We lived in a large terraced house around a square in Hampstead Garden Suburb. The house door was always open and the children played in the central lawn with the other children in the square. It was a fantastic time, a very happy time for me. I used to paint in the loft but I was still collecting recipes and also cooking, trying and re-trying recipes to make them work – because the instructions and quantities were not very precise. We were also always inviting friends over to eat – we had a long refectory table and my children used to make a lot of meatballs.

“As the children were growing up, I was still totally smitten with gathering recipes. I went to the British Library to look for Arab cookbooks but there wasn’t anything contemporary. The librarian found three medieval Arabic manuscripts of culinary manuals that had been found in Baghdad, Damascus and Andalusia – they had some annotations and translations made by scholars in the 1940s. I was beside myself with excitement because I realised they had similar names and ingredients to the recipes we were still cooking. And that is how I became fascinated by the history and origins of dishes and the cultures behind them. When I could find a babysitter, I would also go to the SOAS Library, even though I wasn’t a student there, and they allowed me to borrow books and read books about the Middle East to make sense of where this food derived from. My parents had not allowed me to go to university, as they thought I’d never be able to get married if I did, so I got impassioned about studying history by myself, through food and learning about all those countries.”

Chapter Four: My First Cookbook & Earning A Living

“After my third child was born, I decided to turn the recipes I had collected into a book. In those days, writing about food was not glamorous. We had Elizabeth David and Jane Grigson, but they were the exceptions. People were horrified and would say, ‘Why don’t you paint instead?’ And when I told them I was researching Middle Eastern food, they’d say, ‘Aaargh, isn’t it all sheep’s eyeballs and testicles?’ There was an idea that that kind of food was disgusting, which is why I included poems and stories to show that the recipes came from a culture that is rich and beautiful. A Book of Middle Eastern Food came out in 1968.

“Writing about food is how I supported my family after my marriage broke up in 1974. I was a single parent and the sole earner with no help, not even from my parents. I approached magazines and newspapers and wrote for them, and I also published more books. It was the only thing I knew but I found it so interesting too – I really enjoyed the research, and testing recipes by inviting friends to come and eat became the way I worked. I also gave cooking lessons in my house and I learned a lot from that. My children and friends’ daughters were my little helpers!

“I was approached by a rich investor to open a chain of Middle Eastern restaurants – he was Jewish from Iraq and he had a lot of money to invest but I refused because I wanted to be at home for the children. Their father had left the country and, even though I had my brothers and my own parents, I was the only parent around for my children. The world of my childhood had disappeared, my extended family had dispersed around the world, so my own family was the most precious and important thing I had. I saw my role as mother and nurturer, and I liked that. For quite a long time, I just continued to work at home.”

Chapter Five: Travels Around The Med

“I was still in my 40s when my children left home, and I had already decided that when that day came I would travel around the Med. I could speak the languages and felt I belonged everywhere. Researching food gave me a mission that allowed me to be in places at a time when a woman travelling alone was peculiar – everyone kept asking me, ‘Where is your husband?’ or ‘Haven’t you got children?’ But it opened doors because I was researching home cooking, and at the time it was only women who cooked for their families. I was looking for regional food which you couldn’t find in restaurants because the grand restaurants everywhere were serving French cuisine. It was rare to find regional foods, except in the occasional Italian trattoria – as it was the beginning of tourism, they mainly had tourist food which wasn’t very good.

“On my first trip, I went to Morocco. I had some contacts there from the square we had lived in when the children were growing up and we had become friends. I went to stay with them in Marrakech and they passed me on to their relatives from city to city. I didn’t waste a minute and accosted strangers in cafés, on trains, in the street, on a bench… I would say ‘I’m an English food writer researching your cuisine’. It was my routine starting point and my way of working for decades. But if someone accosted me, I would ignore them because it was usually a man. I remember a man in Morocco started talking to me on a train and I just knew it wasn’t in a nice way, so I asked him if he had any recipes. That stopped him! In some countries, I would say I have four grandchildren and they quickly moved away!

“While I was travelling, I was asked by the BBC to work on a television series and book called Claudia Roden’s Mediterranean Cookery. It was very exciting to work as a team. Then the Sunday Times Magazine asked me to do a series on the regional foods of Italy which they called A Taste of Italy. It was the best job I ever had, travelling to every region in the course of a year and spending a week in each. The editor told me to go everywhere, eat everywhere and bring back as many recipes as possible, as well as stories that men would enjoy reading – in those days, cookery writing was reserved for the women’s pages and he wanted to change that. It was the most fantastic offer and, luckily, I spoke Italian; wherever I went the locals thought I was an Italian from abroad as my accent was from Friuli because of my nanny. The food of Italy was an absolute joy and several publishers asked me to do a book and that went to auction. I was also writing for the Sunday Telegraph – they asked me to write about the food in 15 cities around the world. That was a joy, too.”

Chapter Six: My Book Of Jewish Food

“After my Middle Eastern book came out, I was asked by Jill Norman, my publisher at Penguin, to write a book about Jewish food. It took me 16 years to find the recipes, put things together and write it. This too became a passion and an obsession – I couldn’t stop because there were always Jews somewhere else. At the same time, I continued to write my other books, so when I was in Italy, for example, I would find Jews in different regions – in Venice, the man at the synagogue in the ghetto told me to go to the old people’s home because there were women there who came to the synagogue on Saturdays to cook Jewish dishes. In Puglia, I also found Jewish dishes by chance – and that is why it all took so long. It was all about the recipes that were passed down from mother to daughter in Jewish families over the centuries. They represented dishes from countries throughout the diaspora and they are packed with history and emotional baggage – for me, they are very emotional and very moving.

“The book eventually came out in 1997. It put Jewish food on the map and changed the culinary landscape for good. And of course, what is interesting is that these recipes have been turned into fashionable food by Israeli chefs abroad, especially in London. Twenty-five years on, a special anniversary edition of the book, including some new material, was published in May.”

/https%3A%2F%2Fsheerluxe.com%2Fsites%2Fsheerluxe%2Ffiles%2Farticles%2F2022%2F09%2Fclaudia-roden-image-1.jpg?itok=mbSxgjI6)

Chapter Seven: An Early Influencer

“When chefs and restaurants stopped doing French cuisine and started using cookbooks by Jane Grigson and Elizabeth David, I realised they were using mine too. The owners of Moro, Sam and Sam Clark, have told me they started cooking from my books when they were 14. Sainsbury’s would call me and ask me what they should be stocking – I told them chickpeas, bulgur, couscous, filo, pittas. Two young men from the Fresh Olive Company (now Belazu) came to see me to ask what they should buy – the answer was harissa and preserved lemons. About 18 years ago, my grandson went to a deli in Belgravia and noticed that the food they were selling was similar to what I was cooking at home for the family – it turned out to be one of the first branches of Ottolenghi. In fact, the first time I met Yotam, he confided that my books were his favourite bedside reading. He also told me that when he came to the UK to study, people asked him for recipes from his culture and he used lots of recipes from my book to give people! Today, everybody has all the ingredients like sumac, pomegranate molasses and za’atar that early on nobody could get – the things my books used to say you won’t be able to find. It’s another world of food now. So many younger chefs have been influenced by my books but now I'm influenced by them — because I go to their restaurants and I see what they're doing."

Chapter Eight: Later Life

“Cooking has been my way of enjoying life and learning about the world through food and making friends through food. For me, there is always a feeling of conviviality around the table, a place of fun where I am happy. When I reached 80, I could no longer travel on my own to research as I had done, but I realised that what I enjoyed most in the world and what I’d be able to do at 80 and beyond is cook, and have friends and family round. And that is what I did. But I also have to have a challenge, so I decided to turn this joy into a book with the best and easiest recipes. I knew I didn’t have the strength to cook with heavy pans and I also wanted to be with friends while I cooked. The result was Med which came out last year. I was told in the March just before lockdown that the publisher wanted the book by September. I got into a bit of a panic. But during lockdown my children couldn’t go to work, the grandchildren couldn’t go to uni and they were all cooking all the time, testing recipes for me. Friends and family abroad would also test for me.

“In fact, I never saw my family as much as during the pandemic. I have a large garden so I set up three tables out there so each of the children could be in a bubble with their own family. They’d bring the dishes they had cooked for us to try and I would come out of the kitchen with my dishes, too, but at a distance; I never went near them and wore gloves so that I didn’t touch anything they had touched. I never stopped cooking and it helped me as I had to cancel everything and could totally focus on the book. And this is how Med came about – and all done on time.”

The Next Chapter

“Over the next few weeks, although the new edition of my Jewish food book came out in May, we are launching it officially this month and I am doing some events to promote it. After that, I think I am going to isolate myself and rest. I want to do a Middle Eastern book again, so I am going to think about that. My original Book of Middle Eastern Food came out in 1968 in the days when no one had eaten an aubergine, let alone cooked one, and we didn’t have food processors or blenders and it was all pounding by hand. I have so much more material now and have learned a lot from chefs all over the world. I am thinking of doing the favourites of the Arab world and making the recipes easy for home cooks. I am also being asked to write a memoir, but I am a little bored with my story so I want to include the stories from all the people I have met on my travels into this new book. It’s going to be a lot of hard work but when you live alone, as I do, I need to wake up in the morning and have something to do right away. It gives you a focus – and I’ll be able to ask friends and family round to test my recipes.”

The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand and Vilna to the Present – 25th Anniversary Edition was published in May by Viking, Penguin. Click here to buy.

DISCLAIMER: We endeavour to always credit the correct original source of every image we use. If you think a credit may be incorrect, please contact us at info@sheerluxe.com.